Today, mine closure is about delivering outcomes with real impact on the bottom line, and tangible benefits for all stakeholders. Box-ticking exercises of the past must make way for impactful, sustainable solutions that demonstrate business value unequivocally. Delivery and cost pressures prevail as always, but with the critical nature of mining taking center stage in the global economy, the legacy issues of the abandoned mines of the past continue to shape the public’s perception of the industry. At the same time, regulators, investors, and communities demand more than just risk reduction, ensuring that mine closure, today, generates outcomes that matter.

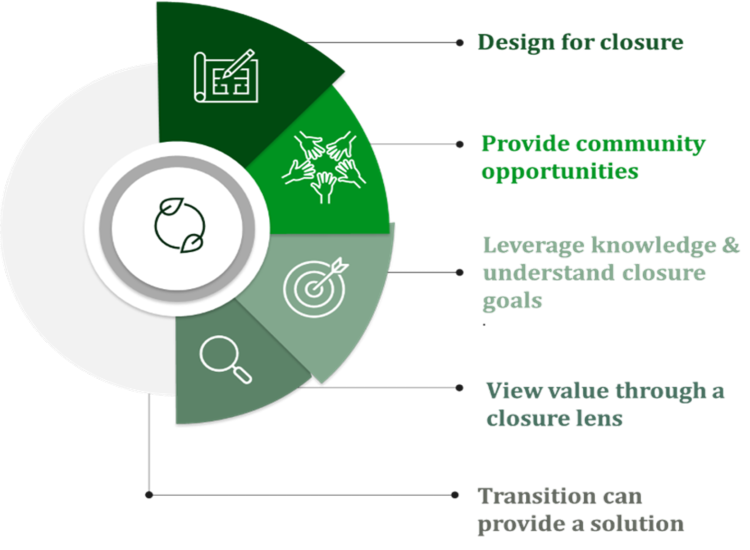

Below, we outline how companies can improve closure performance across five areas. These key recommendations are designed to build business value through improved investor and stakeholder confidence in the industry.

1. Make early closure planning meaningful

While closure planning is integrated within permitting and is a requirement of the exploration codes, it is typically siloed and disconnected from everyday project decisions which are constantly evolving. As mines move from exploration to operations, closure thinking tends to fade, missing critical opportunities to shape its design for better long-term outcomes. Early closure plans are often generic, with limited influence on infrastructure or land use decisions. Design teams naturally focus on efficiency and production; but without integrated closure thinking, legacy decisions can result in higher costs, community resistance, and negative environmental impacts.

Figure 1: Key touch points for an integrated mine closure

Source: ERM

Embedding closure into mine design from the outset changes the game. Treating the full mining lifecycle as a capital project can enable smarter choices—like where to place waste rock or how to plan for post-mining land use. By aligning teams early and applying a structured closure gate process – ensuring all decisions through the life cycle are considered with a closure lens - companies can evaluate options with a clear view of long-term value.

A well-designed mine should deliver more than production; it should be designed with an understanding of the full mining lifecycle which inevitably involves closure. It considers its stakeholders, the final landform, its stability and ecological function and its suitability for post-mining land use its ultimate beneficiaries. There should be no disparity between mine planning and closure planning.

2. Make closure an everyday activity

Every mine that opens will one day close. Yet too often, closure is treated as an afterthought—disconnected from day-to-day operations. In practice, closure outcomes are shaped by every operational decision made along the way. Misalignment between operations and closure goals leads to legacy issues (e.g. pollution inventory and implementation of responses to deal with contaminated sites early rather than as a closure aspect, alignment of monitoring programs, including knowledge management and social programs), inflated costs, and reputational risks.

Progressive rehabilitation is one solution, but without careful planning, it can be undermined by operational activities, like vehicle damage, weed invasion, and poor material controls, which force rework and drive up costs. Instead of seeing mining as just extraction, leaders in the industry now recognize it as a large-scale waste management challenge. Material placement, segregation, and geochemical controls are not peripheral, they are central to reducing closure liability.

Equally critical is collecting and monitoring data. Mines that see monitoring as a regulatory commitment often find themselves flying blind at the time of closure. Maintaining a strong knowledge base and being able to see trends as they emerge throughout the life of a mine avoids duplication, enables smarter decisions, and lowers risk.

3. Understand your closure goals and have pragmatic delivery steps

Mine closure is a classic “wicked problem”—a complex challenge involving interdependent social, environmental, and engineering dimensions. Competing priorities from diverse stakeholders must be balanced, often requiring trade-offs between ecological preservation, economic viability, and community expectations. For example, preserving rare plant habitats while managing waste rock placement demands thoughtful planning and compromise. Successful closure is no longer defined solely by regulatory compliance; it must also reflect environmental, social, and cultural values. Ongoing work in northern Ontario demonstrates how community engagement can shape post-mining land use and workforce transition strategies, ensuring that closure outcomes are meaningful and locally relevant.

Over the past decade, there has been a broader shift in industry thinking toward integrated, adaptive, and sustainability-driven mine planning. Central to this evolution is the adoption of performance-based frameworks—such as lifecycle key performance indicators (KPIs)—that enable adaptive management and continuous alignment with closure objectives. This is complemented by a growing emphasis on natural capital, where ecosystems and biodiversity are treated as assets that need to be restored and enhanced, not as merely liabilities to be managed. Integrating and recognizing the depth of Indigenous knowledge systems are also of critical and expanding importance, including in shaping revegetation and reclamation strategies that are both ecologically resilient and culturally meaningful, especially in the context of climate change.

At the same time, technological innovation is transforming closure planning. Tools such as AI-driven orebody characterization and hyperspectral analysis are enhancing the precision and foresight of closure strategies, allowing for earlier identification of risks and more targeted remediation.

4. Focus on the impact of risk and uncertainty on closure cost

Closure costs are often significantly underestimated during the early stages of mine planning, leading to substantial financial challenges at the end of a mine’s life. This underestimation is frequently the result of siloed risk assessments, incomplete data on site conditions, and overly optimistic assumptions about rehabilitation success. The willingness to dig into the details of those costs early on is often lacking.

Old technologies and outdated cost models fail to reflect the evolving nature of closure liabilities, which change over time in response to regulatory updates, the impacts of climate change, and shifting stakeholder and shareholder expectations. The lack of integration between technical and financial planning further exacerbates the issue, as cost models are rarely updated or stress-tested to reflect these dynamic conditions. Consequently, closure planning often becomes reactive, with deferred responsibilities and legacy issues inflating costs (and cost increases up to five times are common, sometimes running into billions of dollars).

Investors are becoming concerned by the global decommissioning challenge and the growing exposure to closure-related risks, which requires an understanding of what is being disclosed, what the gaps are, and what innovative financing options are available to manage the liability. These concerns are particularly acute in regions where closure funding is tied to revenues from other operations, a model that becomes increasingly fragile in the context of portfolio divestments and Just Transition expectations. Late-stage closure planning examples across the globe highlight the consequences of poor early estimates and underscore the need for expert re-evaluation and more rigorous financial planning throughout the mine lifecycle.

Image 1 – Redevelopment of the Vale Refinery, Acton London

Source: ERM

To address these challenges, the use of probabilistic cost modelling approaches is recommended, such as a Closure Risk Assessment framework, which incorporates scenario planning and uncertainty analysis. Emerging technologies, including digital twins, GIS-based costing, and machine learning, are also enhancing predictive capabilities, enabling more accurate and adaptive in closure cost forecasting. When combined with a risk-based approach to technical methods and robust knowledge management, these tools support a shift from static, compliance-driven models to dynamic, forward-looking strategies that ensure financial resilience and sustainable closure outcomes.

5. Unlock regeneration and transition opportunities

Regeneration presents a powerful opportunity for mining companies to lead a Just Transition and shape what comes next. While companies are well placed to initiate planning, build partnerships, and provide structure, long-term success depends on collaboration with regional actors better equipped to lead regeneration. This requires sustained investment and a shift in mindset: from an obligation to value creation.

Mine regeneration presents an opportunity to work with stakeholders to develop a compelling vision for post mining land use from the outset of a project. In some cases, particularly where the life of mine is relatively short, the regeneration vision can become a positive focal point for community engagement.

Post-mining land use (PMLU) is central to this transition as is an ecosystem model that helps identify development constraints and uncover where social, environmental, and economic value can be created. Quick fixes will not deliver; true regeneration demands strategic foresight, creativity, and long-term stewardship.

Effective closure planning must be built around a deep understanding of stakeholder and rightsholder priorities. Communities should be involved in co-creating the new reality. Transition planning must also address potential community dependencies on mining (e.g., transport and healthcare infrastructure) and invest in transferable skills through retraining and capacity-building.

Image 2 - Community need for Closure Engagement and Just Transition (graffiti on the side of a mine in Colombia)

Source: ERM

Across our work, real-world regeneration has taken shape: in Turkey, wine production has reimagined former mining infrastructure; in arid regions of South Africa, operational water systems have become critical public assets. Indigenous partnerships, benefit agreements, and land-use planning in places like Panama and Argentina have shown how regenerative approaches can deliver long-term social and environmental impact.

For mining leaders, the takeaway is clear: closure done right becomes a legacy that outlives the mine.

Conclusion

Mine closure is more than stabilizing land and managing risk; it is the final, lasting impression a mining company leaves behind. It should be seen as a strategic opportunity to create long-term value for communities, ecosystems, and shareholders alike. Poor closure outcomes stigmatize the industry.

Success depends on realistic cost forecasting, understanding community priorities, and planning for productive post-mining land use. In other words, closure is about understanding an end point and what steps need to be undertaken to deliver this i.e. having a clear vision, an understanding of success and the right KPI’s that continue to provide momentum on the journey towards closure.

As scrutiny intensifies and closure liabilities grow, mining companies that invest early, plan holistically, and partner for regeneration will be the ones that lead—leaving behind not just a closed site, but a positive legacy.

Further reading

If you would like to explore these issues further, come and meet our experts at the forthcoming ACG Closure conference in Lulea, Sweden (23-25th September).

Additional resources developed by the ERM team can be found below.

Defining success in closure

- The role of key performance indicators throughout the mine life in achieving closure objectives

- Meaningful evaluation of rehabilitation and closure in the early stages of the mine lifecycle

Unravelling the cost of closure

- Sustainable finance and the role of mine closure

- Mine closure liability as an environmental, social, and governance concept: using a multi-dimensional approach to mine closure liability reduction

- Using uncertainty analysis to unravel cost risks for nuclear and mine site closure

Just Transition & Post Mining Land Use